Shortly after my diagnosis, I made the decision to let all

my relatives know about it. I had,

admittedly, done a pretty poor job of keeping in touch with everyone over the

years. We might see each other for

dinner when we were visiting New England or maybe exchange an email here and

there, but not much else.

When my Auntie Nina passed away at 100 years old in 2020,

that meant all our relatives from that generation were gone. Years earlier, we had lost my cousins Lee and

Joyce. Our family shrunk more when Joyce’s

son Michael, my second cousin, succumbed to brain cancer in 2023, followed by

my godmother and cousin Barbara dying of kidney disease the next February. I didn’t like the fact that I was mostly

seeing my cousins at funerals, so I saw my diagnosis as a potential way to

start regularly communicating with them—before we lost anyone else.

I figured it was easiest to just create an email list containing

all the cousins I had addresses for and send a message explaining my

situation. I got such positive responses

from them that I kept sending periodic updates.

These exchanges ultimately led to in-person visits, resulting in my

feeling closer to my cousins than I had in years. This was definitely a positive that came out

of what could have been very negative circumstances.

My urologist’s office had said they would send all my

information to AdventHealth in Orlando and they would soon contact me to set up

an appointment. While waiting for that

call, I started reading the book the urologist had loaned me. I quickly finished it and learned many things

but, overall, I found it lacking. First,

it was about 6 years old, so I knew it did not have the latest

information. Second—although I don’t

think I’m biased against female doctors—I wondered, at least subconsciously,

why a woman was writing about something that is exclusively a man’s problem. So maybe I was biased against the book to

start.

Towards the end of the book when side effects—especially

worst case ones—were discussed, there was a line that said something to the

effect that: if you can’t have sex anymore you can still hold hands. I’m sure the author was just trying to say

that, if the side effects were bad, it still wasn’t the end of the world, but

the sentiment somehow felt condescending.

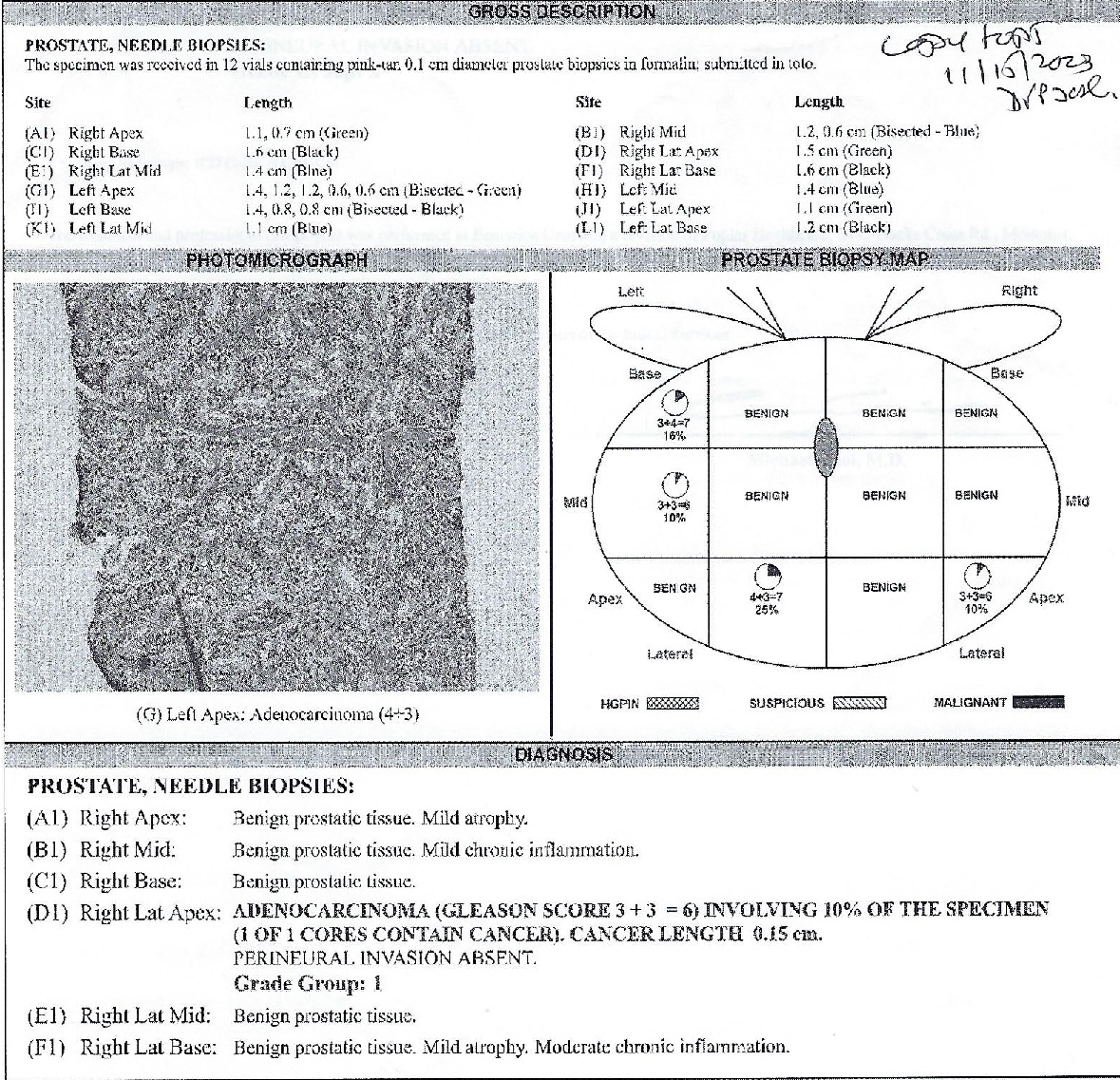

During this waiting period I also spoke to both my brothers and my friend, Jim, about their experiences with prostate cancer. All of them had opted for surgery. I got copies of the data they had received from their biopsies and subsequent appointments. I read through their biopsy reports which detailed things such as how many of the 12 samples, or “cores,” from the biopsy contained cancer as well as the severity, or Gleason score, and size of each cancer occurrence found. I believe I also looked at an MRI report that my brother Walt had. At this point, I had none of this data. All I had was my urologist’s verbal declaration that I had “borderline bad boy cancer.”

Unsatisfied with the information from the loaned

book, I

sought out something better from—where else—Amazon.

I found what I was looking for in “Dr.

Patrick Walsh’s Guide to Surviving Prostate Cancer,” a current-year

update to a

book by the pre-eminent prostate cancer doctor, Patrick Walsh. Note that the book was updated by a woman,

Janet Farrar Worthington, so I guess I had gotten over whatever bias I

might

have had against female prostate cancer experts.

While continuing to wait for the call from the

surgeon’s

office, I dissected the book, making notes and jotting down tons of

questions. All the information, in my

mind, confirmed my belief that things were moving a little fast.

First, a second reading of the biopsy should be

done before

anything. Apparently, interpreting the

images from the biopsy and assigning a numeric score to each cancer

requires

some level of judgement by the person reading the biopsy.

Because there is subjectiveness in this

effort and human beings sometimes make errors, a second person should

review

the biopsy.

Second, I found that modern best practice would

have been to

perform an MRI prior to the biopsy, rather than just an ultrasound as

my

urologist had done.

I also discovered there are new scanning

technologies that

can better define and characterize the cancer.

There is even a special scan—a PSMA-PET scan—that can

essentially detect

prostate cancer anywhere in the body where it might exist and thus

definitively

determine if the cancer has spread.

There are also genetic tests that can further define elements

such as

the likely aggressiveness of the cancer.

None of this information was in the older book.

The Walsh book also had much more current detail

about the

three basic prostate cancer treatment options: surgery, radiation and

hormone

therapy. In cases where the cancer is

not aggressive, there is also an option to, essentially, do nothing and

monitor

the cancer to see if it is growing to the extent that treatment is

necessary.

I was somewhat familiar with hormone therapy from

my

father’s experience with it over 20 years ago.

He chose this option because he was in his 80s when he was

diagnosed and

had other health problems, making surgery or radiation unwise,

impossible or

unnecessary (i.e. he would likely die of something else before the

prostate

cancer got him). Back then, I believe

estrogen was the typical hormone treatment and it resulted in expected

side

effects such as hot flashes.

A side effect less mentioned was that the hormone

treatment

also weakened his bones, resulting in terrible osteoporosis. Because of his weakened bone structure,

several of his vertebrae fractured over the years and became a source

of

constant pain for him.

The “solution” to the osteoporosis was infusions

of Zometa,

a drug produced by Swiss pharma giant Novartis that is often used to

treat bone

cancer. These treatments had the

unexpected—and unadvertised--side effect of bisphosphonate-related

osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ), or jaw necrosis.

Essentially his teeth and parts of his jaw

started rotting and falling out. We only

found out the cause of this from his dentist, who had heard about this

Zometa

side effect. In fact, he had other

patients with the same problems.

When my parents told the doctor delivering the

Zometa to my

father what the dentist had said, the doctor apparently said something

like the

Zometa was doing more good than harm.

So, being folks that believed in taking the advice of “smart”

doctors,

my ma and dad decided he should continue the treatment.

Eventually, my father’s teeth got much worse,

making it

difficult for him to eat. The doctor

finally agreed that the Zometa should be stopped, but the damage had

already been

done.

At some point, dad was so upset about his teeth

falling out

that he asked me if he could sue anyone over his situation. Consulting Mr. Google, I quickly found that

there WAS a multi-jurisdictional lawsuit on this exact side effect of

Zometa. So I contacted the law firm

handling

the case and they were very excited to take dad on as a contingency

client—we

would pay nothing and they would get 40% of whatever settlement was

received. I remember the person to whom I

spoke saying

that dad’s case was solid, with all sorts of documentation of the

problem. He said the lawsuit was “in the

red zone” (the

football red zone, not like a warning on a tachometer) and that the

expected

average settlement would be north of a million dollars.

Apparently, Novartis decided to fight the case

rather than

settle, so it wasn’t in the “red zone” as much as we were led to

believe. The fact that this case was not

certified as

a class action suit meant that there would be trials for each

individual

plaintiff until there was a settlement or until the folks suing died

and/or gave

up. The case dragged on for years and

results in the courts were mixed with some wins and some losses.

|

|

Every now and then, dad would receive information or

inquiries in the mail regarding the case.

He was living by himself and close to 90 years old by now. Talking with him on the phone one night, he

told me he had received a questionnaire about the lawsuit in the mail. I urged him to wait for my next visit so I

could look it over, but he insisted on filling it out and returning it on his

own, even though he really didn’t understand all the questions. As it turned out, the questionnaire was from

the defense attorneys. Sometime later,

he actually had to be depositioned and the defense attorney was relentless in

making him sound foolish due to his questionnaire answers. I was allowed to listen in on the deposition,

but not say anything, which was very frustrating.

From the defense attorney’s questions, I could

tell dad’s

case was going to be doomed by the fact that he had found out what the

drug was

doing to him (from his dentist) but continued the treatments. Apparently, the lawsuit was also filed too

long after he stopped treatment. Ultimately,

dad died before the case was resolved and, although we were given the

option to

continue, we just dropped it.

As it turns out, in addition to selling dangerous

drugs

without warnings, Novartis was busy with flat out fraud as well. In 2020 Novartis paid a $642 million

settlement for bribing doctors and patients to use their drugs (you can

read

about it here). If you wonder

why Medicare

is becoming insolvent, at least part of the reason is corrupt companies

like

Novartis who are ripping them off for hundreds of millions of

dollars—I’m sure

they’re not the only ones.

But I digress.

Although the lawsuit was not a positive

experience, I did

learn some things. One was that I saw

first-hand how relentless Big Pharma lawyers can be.

The guy who questioned dad had no problem

humiliating an old man and he probably got a bonus when my father died

and our

case was dropped.

Another thing I learned is that you cannot just

take

information or advice provided by doctors or drug companies on faith. When you have a medical condition, you really

need to do research and “become your own advocate.”

As a side note to a side note to a side note, many

years

later I saw an interesting episode of one of my all-time favorite TV

shows, “American

Greed.” It was about a scamming

attorney

who won big settlements for clients who never saw the money. He embezzled it from them to fund his lavish

lifestyle. The law firm was Girardi and

Keyes—the ones who handled my father’s case.

So maybe it was good to know that we never really missed out on

that

million dollar settlement as the money would have gone to fund

Girardi’s

yachts, luxury homes and cars.

|

|

All of dad’s medical problems in his latter

years—hot

flashes, osteoporosis, cracked vertebrae and rotting jaw and teeth—all

stemmed

from his taking hormone therapy for prostate cancer.

My brothers and I have wondered whether dad

might have had a better quality of life if he had done nothing about

his

prostate cancer. Perhaps, with the way

prostate cancer is thought of today, that might have been the

recommended

option.

So that was a series of major digressions and

rants to

explain my going-in concerns about hormone treatments for prostate

cancer, as

well as why I might want to do my own research rather than blindly

accept the advice

of the first doctor with whom I talked.

As it turns out, hormone therapy alone is really

only used

as a primary treatment for people in really bad shape who have no real

hope of

being cured or for older patients, like my father, whose age and other

health

conditions make surgery or radiation impractical and difficult to

impossible. So, hormone therapy alone

would not be an

option to treat my cancer.

At this point I realized I had two viable

treatment options:

radical prostatectomy—surgical removal of the prostate—or radiation

therapy. I found that, although surgery

had long been considered the “gold standard” of prostate cancer

treatment, a somewhat

recent study found that radiation therapy was just as effective as a

cure. The fact that radiation is an option

that is

as curative as surgery seemed unknown by most, including my primary

care

doctor. Most thought radiation was only

used in older patients who might not have a long life ahead of them.

While I was reading and digesting the information

in the

book, I realized I needed my records from my urologist to determine how

severe

my cancer was and what my actual options were.

I also realized it had been a week and I hadn’t heard from the

surgeon’s

office yet so I gave them a call. The

person I talked to assured me that, if I had been referred, I would be

getting

a call soon. After another week went by,

Thanksgiving had passed and I decided to call them again.

They said they had no record of a referral

for me, but would send me an 11-page application to fill out if I was

interested in becoming a patient. They

also said I needed to get my records from my urologist and send them

with my

patient application form. I wondered why

my urologist’s office had not done all this already.

So I started filling in all the historical medical

information and family history that the form requested.

I remember being annoyed that, rather than an

electronic form, they sent you one you had to print out, fill in by

hand, and

scan back in. While I was working on the

form, I called my urologist’s office to ask about getting my records

but, for

some reason, I couldn’t reach them—no one answered and no voice mail. I decided to drive by the office, figuring I

could return the book the doctor had had loaned me while getting a copy

of my

records. This attempt also failed as I

found the office closed on a Wednesday afternoon, making be wonder if

they were

still in business.

Eventually I found the office open and explained that the surgeon didn’t have my records, plus I wanted a copy of them for myself. They told me they couldn’t just print out my records and hand them to me. They needed to be signed by the doctor, or something, and date-stamped. That seemed ridiculous as they were my records and I (and my insurance company) had paid for them, but I wasn’t going to create an incident over it so I waited some more.

While there, I also asked about sending my biopsy

results off

for a second reading, which all the books recommend.

They just said, of course, that the surgeon

would handle that. It seemed pretty

clear that they had already “handed me off” as a patient.

About a week or so later, the office called to say

my

records were ready. I zipped down there

to pick them up. When I did, they

assured me that, this time, they were being sent to AdventHealth.

By the time the records were ready, I had already pretty

much finished reading the second book and was anxious to get my data so I could

characterize the cancer more definitively than “borderline bad boy

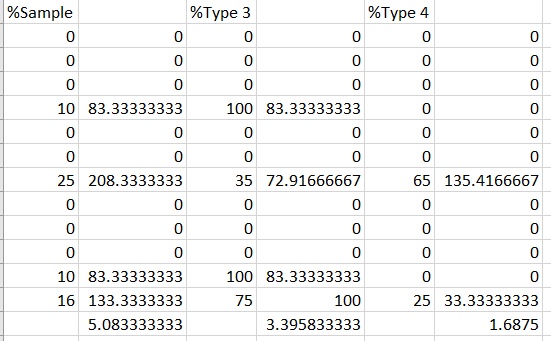

cancer.” I had learned that the key

number was the Gleason score, a measurement of how organized, or aggressive,

the cancer is. A score of 1 or 2 means

no cancer (and aren’t actually used anymore), 3 is not so bad, 4 quite a bit

worse and 5 the worst. The actual

Gleason score is a sum of the 2 most dominant types of cancer in each positive

sample so, if a sample is, say, 25% 4 and 10% 3, the score for that sample is 4

+ 3 = 7. So the overall Gleason scores

run from 6 to 10 but, within the scores there are differences with, for

example, a 4 + 3 worse than a 3 + 4 because the 4 + 3 has more aggressive

cancer. The overall Gleason score is simply the highest score of all positive

samples.

To better summarize prostate cancer, they

eventually came up

with a grading system that assigns a 1 to 5 score (5 being worst) based

on the

Gleason scores. The grade also makes it

much easier to explain to people how bad the cancer is.

Examining my records, I found that 4 of my 12

biopsy samples

had cancer with the grades being 1, 1, 2 and 3 for an overall grade of

3 of

5. The other information in the biopsy

included the size of each cancer, the size of the prostate and whether

there

was evidence of cancer escaping the prostate (there was not, which was

good).

I parsed the data every way I could, including

creating a

spreadsheet to calculate the percentage of my prostate that had

different

cancer types. Turned out, by my

calculations, only about 3 ½ percent of my prostate had cancer and only

a

little over 1 ½ percent was the bad one—so how hard could it be to

treat that

relatively small amount, I thought.

Turns out there is also a “stage” for prostate

cancer, but

it seems less relevant than the grade. I

calculated my stage to be T1c, meaning the tumor could not be felt via

a rectal

exam and had not metastasized (spread).

That sounded good, too.

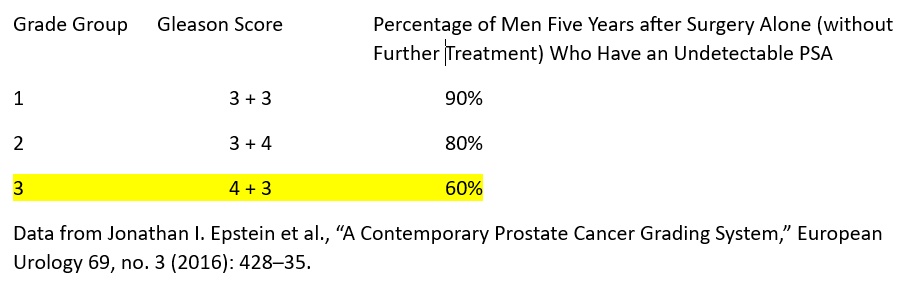

More sobering was a chart I found in the book that

showed

that, with grade 3 prostate cancer, 5 years after prostate removal,

only 60% of

patients had undetectable PSA. In other

words, the cancer came back within 5 years for 40% of men with grade 3

cancer—my grade. And with my luck, that 40% felt like 99%.

By the way, in case there weren’t enough numerical

ways to

characterize prostate cancer, there is also a verbal description. Mine was the rather ominous-sounding

“unfavorable

intermediate.”

So now I knew more about my cancer.

The first takeaway was that it could not be

ignored, so the “watchful waiting” option was out.

From all my reading, I knew there were two

ways to cure it: surgery or radiation, although I still needed to talk

to a

specialist to know if radiation was truly a viable option.

By now, I had created pages of notes from my

reading and had lots of questions about potential treatments.

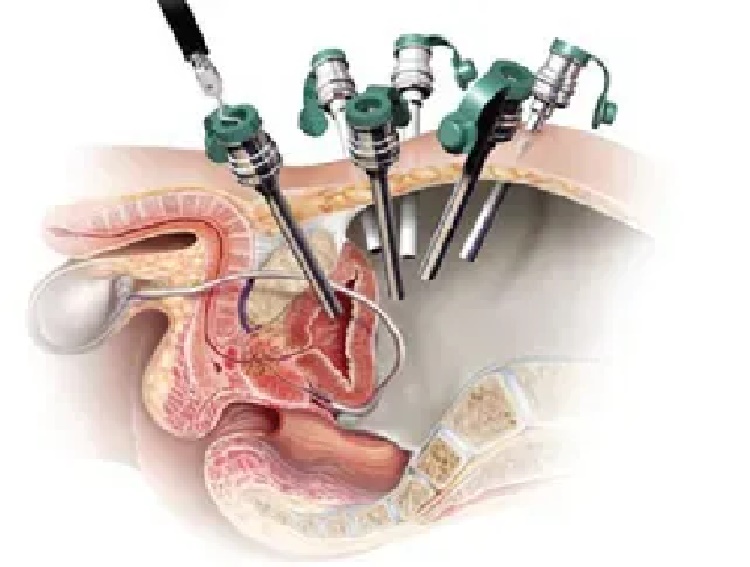

From my brothers and my friend Jim I already knew

surgeons

pretty much no longer do the cutting directly when performing ordinary

prostatectomies. Instead, a robotic

device, called a Da Vinci, is operated remotely by a surgeon. The surgical tools are inserted through small

holes cut into the abdomen. In my mind,

I envisioned the surgeon looking like he’s playing a video game or

maybe using

one of those arcade crane games where you try to grab a good prize.

|

|

The book was very helpful and gave me an

appreciation of

what my brothers and friend Jim had gone through. However,

several times while reading it I had

to stop and put it down. The passages

describing the details of the surgery were just too upsetting for me to

get

through. I believe both my doctor and

the book referred to URLs where you could watch videos of actual

prostatectomy

surgeries. Who the heck would want to

see that?? Probably a lot of people, I

guess, but certainly not me.

The other difficult thing for me while educating

myself was

the realization that there were no great options to cure prostate

cancer. Each approach had unavoidable

risks and

unavoidable side effects. With surgery,

you have to worry about blood clots, infections and hernias, as well as

the

risks all surgeries bring. With

radiation, there is the risk of the radiation damaging adjacent areas,

especially the rectum. Radiation also

could bring fatigue and urinary frequency.

Both options bring long term potential urinary incontinence and

impotence. Further, given my grade of

cancer, with radiation I likely was looking at temporary androgen

deprivation

therapy (ADT), aka hormone treatment, with (hopefully temporary) side

effects

such as hot flashes, more fatigue, weight gain and loss of muscle mass. I realized that, going forward, my life would

be different—some things would not be as “good” as they were in that

moment, no

matter what option I chose.

I guess, in my mind, I was always somewhat biased

against

the surgery option. I think, given a

choice,

most people would avoid surgery—or at least delay it as long as

feasible. Although surgeries are very

routine and

millions are probably performed every day, there are still inherent

risks.

Years ago, early one evening, I got a call at work

from

Pat. One of her best friend's husband

had been in the hospital for knee surgery, but there had been

complications

with the anesthesia and he was in grave danger.

She asked me to come to the hospital for support.

Initially, I said no as this was not long

after my mother, Pat’s mother and several other family members had died

and

I just didn’t want to go to another hospital.

Ultimately, I did go, however.

It was after visiting hours and I had to use a

back entrance

and walk a long way to the room. When I

finally got there, I saw the husband lying motionless on the bed. However, every 30 seconds or so, his body

would convulse and his eyes popped wide open.

They said he was brain dead and they were waiting for his sons

to get

there so they could see him before they removed him from life support. My job wound up being to go pick up one of

the sons that was flying in. I was

certainly relieved when I was able to leave the room.

That image of a man convulsing in a hospital

bed after he had come in for simple knee surgery certainly was burned

into my brain

since then. That memory likely

contributed to my anti-surgery prejudices.

The prostate is connected to the bladder and the

penis—two

pretty important things. Radical

prostatectomy removes the prostate, then stitches everything back

together with

the hope that everything still works afterward.

The surgery has become routine and is performed thousands of

times a day

but I still worried, somewhat, that mine would be the one where the

surgeon

made one slip-up and I would be peeing in a bag the rest of my life. Or maybe the hole in my heart and irregular

heart

rhythms would lead to some complication.

Or maybe there’s a problem with anesthesia, as I witnessed years

ago. These types of outcomes are, of

course, extremely rare and these fears are probably not rational, but

they were

still in my mind.

Logically, I’d go in for surgery, they’d do it,

I’d stay in

a hospital for a day or two, and I’d go home with a catheter which

would be

removed a few days later. After that

there would be healing for some time and regular blood work, but,

essentially,

I’d be “done” with treatment after a week or two.

Further, after the prostate is removed, it is

actually

dissected it to determine if the cancer existed on the borders of the

prostate. If that were the case, the

surgeon could go back in and remove more tissue, hopefully keeping the

cancer

from spreading.

Being “done” that quickly assumes that follow-up

bloodwork would

show my PSA remaining at zero which, according to the table cited

above, won’t

happen 40% of the time. In those

situations—as was the case with my brother Walt-radiation would be in

order

but, for the majority of patients, the big stuff is done in a week or

two.

Radiation would be a much longer time commitment. There would be many steps to prepare for

radiation, then daily treatments for several weeks.

After treatment, PSA would need to be

monitored for years to make sure the radiation was effective. If the PSA does start rising too fast, the

whole process, including radiation, would likely need to be repeated. It is unlikely surgery could be performed

after radiation because of the damage the prostate would have incurred

from the

radiation. For these reasons, most men

choose to just “cut the cancer out of me” and be done with it as my

brothers

and Jim had done.

With my records and patient application forms sent

to the

surgeon’s office, I finally got a call to schedule my appointment at

AdventHealth. It would be at the end of

January—over 2 and a half months after my initial diagnosis. By the time of my appointment, I felt really

ready, armed with my pages of notes and all the questions I had

highlighted. The research I failed to do

was finding out what the AdventHealth facility actually did. Because the information package I had

received said I would be meeting with a “team” of experts, I had

assumed I

would be able to ask about all the options for treatment and get all my

questions answered. In actuality, this

facility only does surgery, which I would have known if I had done a

bit more

homework.

The day of my appointment finally came and I took

the hour-plus

drive to Celebration—the Disney-created community outside Orlando. Speaking of Disney, even though I was

following my Google directions, I still managed to make a turn too

early and

found myself in the parking lot of Disney’s corporate offices. Luckily, Disney security did not detain me as

a potential corporate spy and I was able to exit their lot, do some

backtracking,

make a likely ill-advised U-turn and arrive at Advent early for my

appointment.

After depositing my car in the first garage I

found, I looked

at the provided map and started trying to figure out where the building

I was

supposed to go to was in the somewhat sprawling campus.

When walking out of the garage, a young woman

with crutches who might have been a cancer patient asked me for

directions. I explained this was my

first time there, but we ultimately both found the cancer buildings we

were

going to. This was the first time I

actually thought of myself as a cancer patient.

The day started with yet more paperwork, a check

of my vitals

and providing a urine sample before moving to the substance of the

appointment. Over the next couple hours,

I met with several nurses and/or assistants who provided various

information

about prostate cancer and the surgery, a lot of which I had read in the

book. It was somewhere in this process

that I realized this was all going to be about surgery.

I asked the final nurse with whom I met what

I would do if I wanted to consider other options, like radiation. Were there radiation specialists at Advent

that I could talk to? She

said they had no radiation doctors there

but that I could ask the surgeon about it when I talked to him. In retrospect, seems like that would be like

going into a McDonald’s and asking for directions to the nearest Burger

King.

One of the women with whom I met talked to me about getting a genetic test. I was happy to hear this, as I had read how genetic tests could be useful in predicting how aggressive the cancer might be, identifying mutations that could lead to future cancers and possibly warning if other relatives (in my case, my nephews) could be genetically predisposed to prostate and other cancer. I had actually planned on asking if I could get a genetic test done.

They had me fill out an online application for the genetic

test on my phone. That process was a

little dicey as I had a crappy, old phone.

After I was nearly done, something went wrong and I had to re-enter all

the info again. In the end, the

application came back and said, based on my insurance and income level, the

test would cost less than a hundred dollars, which was fine with me.

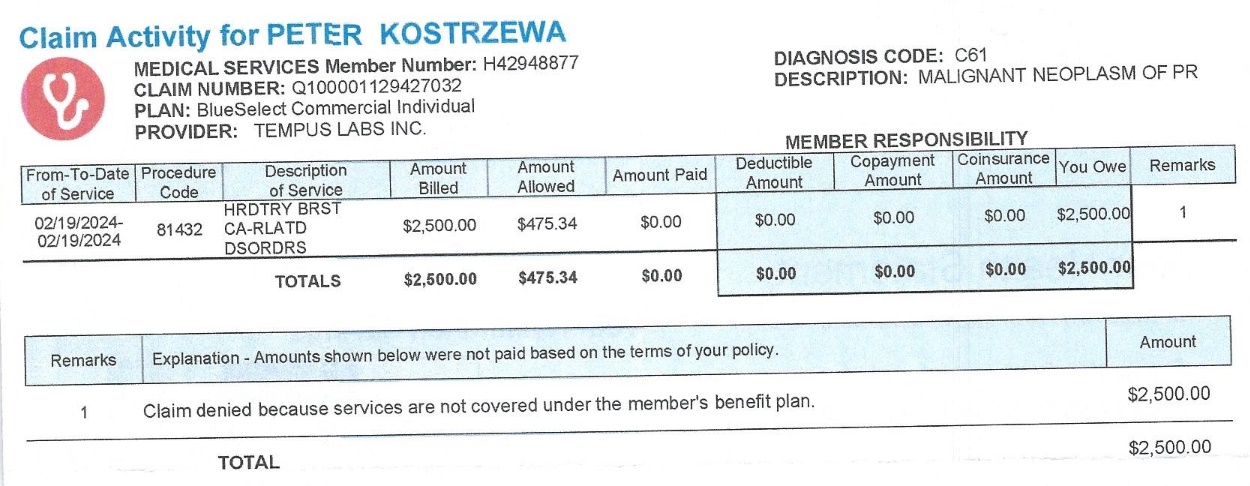

As a sidenote, months later I got an Explanation

of Benefits

from Florida Blue that said the claim for the test had been rejected

and I

could be billed $2500. Around the same

time, I got a letter from the genetic test company with a form to fill

out and

sign authorizing them to appeal the rejection.

I haven’t heard back from anyone asking for the $2500 so maybe

the

appeal was successful. Either way, no

one’s getting $2500 from me for the advertised $100 test.

So, with the application approved, the nurse in

charge then

said she would draw a blood sample for the test. I

was thinking this was really efficient as

everything would be done right then and there. I

was mistaken. The nurse was unable to

complete the blood

draw. It was pretty obvious she hadn’t

done it a lot, as she was muttering instructions to herself. After her failed attempt, she said she would

get another nurse who was an expert at doing blood draws.

The second nurse also failed. All

this surprised me because, whenever I’ve

had blood work, the phlebotomists generally had no problems and some

said I had

great veins.

In total, three different nurses attempted to do

this simple

blood draw and all of them failed.

Finally, they gave up and said they would send someone to my

house to

get the blood sample. I have to say,

this was quite disconcerting. Here were

the nurses that would presumably be assisting with this quite serious

surgery I

was considering but they couldn’t perform a very elementary task. By the way, the nurse they sent to my house

to draw the sample had no problem and, I believe either laughed a bit

or was

incredulous when I told her three nurses failed to complete the draw at

the

office.

Among the questions I asked one of the nurses was

whether I

could get scans using the latest technology I had read about. Specifically, I had read about a

multiparametric MRI that would provide 3D images and, more importantly,

the

PSMA-PET scan, which is designed to specifically detect prostate cancer

anywhere in the body. I felt this would

be hugely significant if I could get one because it could tell if the

cancer

had spread anywhere outside the prostate.

Also, my research had told me that a bone scan was recommended

for

patients with cancer of my grade. The

nurse’s response was that that they never do PSMA-PET scans and

insurance would

never cover it. I guess they assume they

don’t need the PET scan if they’re cutting out the prostate, but this

was another

disappointment.

After a couple hours of these preliminary

meetings, the

surgeon arrived with a couple assistants.

He spent, perhaps, 90 seconds in the office with me. There would be no chance for me to ask all

those questions I had prepared and certainly no discussion of anything

but

surgery. He did assure me that he would

be able to take good care of me and added that the urinary frequency

due to my

enlarged prostate would no longer be a problem—since I wouldn’t have a

prostate

any more. In retrospect, I probably shouldn’t have expected any

more

time with the doctor as I understand he is busy performing

hundreds—maybe even

thousands—of prostatectomies a year.

After the doctor was finished with me, I was

ushered to

another room to meet with a woman whose title escapes me but who I

would

describe as the “closer.” Her job was to

give me the medical orders for things like a chest x-ray and 3D MRI

that I

would need to get before the surgery.

She also provided a checklist of other clearances I would need

from my

cardiologist (which I had actually gotten a couple days before) and my

primary care

physician.

Her job was also to get me to sign all the authorizations for the surgery so it could be scheduled, even though I had told the nurse that brought me there that I was still undecided about what I would do. When I told “the closer” I was undecided and wanted to look at other options, she did not seem happy. I believe she warned that not signing now could delay my surgery date. At this point, I honestly felt like I was being sold a timeshare rather considering a medical procedure.

So I walked out of the building with a list of

things to get

done and a brochure about the Da Vinci machine that would be used in

the

surgery. Thinking about the appointment

on the drive home and thereafter, I felt a bit lost.

I really hadn’t gotten any new information.

I did have the genetic test scheduled and

they gave me a location where I could get the 3D MRI, so those were

good things,

but I really didn’t get any of my questions answered.

Nothing about the situation felt right but I

had no idea where to look for other options.

Who could I find to answer that list of questions I still had? How could I find a radiation oncologist that

I could trust to give me good information about that option?

On my drive back on Route 528, I had the idea of

calling my

brother, John, who was down from Rhode Island and staying in Cape

Canaveral for

a couple months. I felt like talking

about my day with someone who had been through prostate cancer before. When he said he and his wife, Carol, and

their son, Andy, were just hanging out on the beach, I drove over. It felt good to vent a little bit about my

somewhat disappointing appointment.

Verbalizing my concerns helped me focus on starting to come up

with a

plan to address my concerns.

Despite my indecision about my treatment, I still

started

working on completing the items on the checklist I had been given. I figured I’d need to get an MRI no matter

what I decided. Also, I had already had

a cardiologist appointment a couple days before meeting the surgery

team and my

cardiologist had signed off on my going off blood thinners prior to

surgery, so

that was done.

After the AdventHealth appointment, I went to Neuro Skeletal Imaging in person with my orders to schedule an MRI and chest X-ray. This facility had been recommended by AdventHealth since they had a 3D MRI imaging machine. It was called a 3-Tesla machine or something like that and I remembered hoping it had nothing to do with Elon Musk. I wasn’t sure if this machine would do a multiparametric MRI (mpMRI) as I had read about and the staff at Advent didn’t seem to know what I was talking about. I assumed it would be fine as it would be a 3D scan and the name sounded cool enough.

A day or two after the appointment, I answered a

call at

home that showed it was from AdventHealth, thinking it was a follow-up. I guess it was, in a manner of speaking. The gentleman on the line had a heavy

island-sounding accent and proceeded to tell me what a great surgeon I

had and

how lucky I was to get him. I replied

that yes, I knew he was world-renowned and I knew people that had used

him. He essentially kept repeating how

great the surgeon was and I kept agreeing, wondering where this

conversation

was going. This, again, felt like a

sales job rather than a discussion about a medical procedure. Eventually he asked if I was a “man of

faith.” When I replied that I was not

the conversation soon ended. I kept

thinking how strange that call was.

I had noticed that the screen savers on all the computers at

AdventHealth all displayed biblical verses, which I thought a little strange. I didn’t remember seeing anything like that

at any other health care facility I had been to. I only realized after the fact that the

hospital was actually founded by Seventh-Day Adventists (hence the name, as light

dawns on Marble-head me) and was, in effect, a Christian ministry. I guess that’s not unusual as many hospitals

seem to have religious roots. With

regard to health care, I wouldn’t think that was good, bad or indifferent, but

I thought it was interesting and likely explained the phone call and reaction

of the caller.

Another couple days later I received an email from

the

surgical coordinator. The email was also

strange in that, amongst the reminders about the checklist of actions I

had to

complete, smiley-face emojis were sprinkled.

It might be a sign that I’ve gotten old and cranky that smiley

face

emojis in a message about prostate surgery somehow annoyed me.

I replied politely that I had scheduled things

like the MRI

and x-ray but that I was still undecided as to my final course of

action. She replied, amidst more

smiley-faces, that I

should let her know once I had decided.

Apparently, she didn’t really want to know if I had decided

against the

surgery because, when I told her that a month and a half later, she did

not

reply.

A couple months later I got a rather mean-spirited

letter

from Advent Health, chastising me for not completing my pre-surgery

tasks,

stating they tried to reach me many times (they hadn’t) and telling me

I would

now have to start the whole process all over again.

I was puzzled—and a little pissed off—but it

kind of reaffirmed my feelings about that whole situation.

At some point shortly after the AdventHealth

appointment, I

had sort of a mini-revelation. What if,

instead of going for the most convenient or cheapest method of treating

my

cancer, I looked for the BEST place to get it treated.

Even if it meant traveling out of town or

choosing a treatment method that most would not choose.

What if I didn’t worry about cost and did

what my gut told me was the best choice for me?

At that point, I started looking at the most

well-known

cancer treatment centers, like Moffit in Tampa, but then had the better

idea of

specifically looking for the best prostate cancer treatment centers in

the

country. I eventually came up with about 5 that were on most lists:

Orlando

AdventHealth (where I had already been), Johns Hopkins in Mayland

(where

prostate cancer pioneer Dr. Walsh had practiced), Sloan Kettering in

New York,

Dana-Farber in Boston and, I believe, Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville,

Florida. I looked at all their websites

and tried to

determine which had all the latest technology I had read about.

As I did this research, I started thinking about

my 35 years

living in Florida and came to the realization that anyone I had hired

to do

anything in Florida—from landscaping, to irrigation repair, to fence

installation—was incompetent. Okay,

that’s probably an exaggeration, but it is, at least partially, why

I’ve tried

to do so much of this type of stuff myself—despite the fact that I am

NOT

“handy” and mostly quite incompetent myself. Still,

my thinking went, if I can’t trust

anyone in Florida to weed whack my yard can I find a Florida man (or

woman) I

trust to cure my cancer? If they were

the best at what they did, wouldn’t they be working in New York or

Boston or L.A.

or somewhere like that??

My thought process

led me to Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston. I

was very familiar with Dana Farber because,

unfortunately, I have had many relatives and friends who have had

cancer. Those who were treated at

Dana Farber had

only positive things to say about it.

Further, when my good friend Mike was at Dana Farber with

terminal brain

cancer, I spent a day with him and his wife and got to see first hand

what

excellent care he was receiving. They

didn’t even get upset when he kept hitting the nurse call button,

thinking it

was the button that would rewind a TV program on his DVR.

Several who ultimately lost their battles with cancer named Dana Farber as the charity to which memorial donations should be directed. Because of those donations, I had read a lot about Dana Farber in the newsletters they had sent over the years. More importantly, they had the latest prostate cancer technology I was looking for. Also, with Dana Farber being located in my home state, I might even be able to connect with friends and relatives still in the area if I decided to get treated there.

So I decided to try calling Dana Farber. Honestly, I figured they would not take me as

a patient, since my cancer was unremarkable.

I assumed it would be a difficult facility to get into, given

its

world-class status. I also thought my

insurance

would be unlikely to work out of state, making it cost-prohibitive. Still, I called to see what they would say.

I was amazed how efficient the phone call was. After initial collection of my information, I

was transferred to an insurance specialist who looked up my insurance

and

quickly determined that Dana Farber was in my plan.

I then spoke to a scheduler to whom I

explained I would be coming from Florida so it would be great if my

consultations could be set up within a day or two.

Later that day, they called back and had set

up three appointments with a urological oncologist, a surgeon and a

radiation

oncologist, all on the same day and just a little over a month away.

I couldn't believe how quickly this had all

transpired. With a single phone call, and

within a single

day, I had a set of appointments at a top-notch cancer facility. Better still, my insurance would cover those

appointments. So I was really doing

this. I was flying up to meet with

doctors at Dana Farber to try to figure out what to do.

Now, I could have a discussion with doctors

who could give me a complete picture of my treatment options.

I still had over a month to think about all this and get ready for the appointments. I decided to continue completing some of the actions required for the surgery, in case I went that route. Also, I was anxious to finally get some scans done on my cancer and figured they would be useful no matter what course I pursued. Plus, I had already scheduled my MRI and chest X-ray.

I also talked to my brother John and, even though he and

Carol would be getting back from Florida just a few days before I arrived, he

said I could stay with them and my nephews at their house in Rhode Island when I

came up for my appointments. With that

part figured out, I booked my flights and rental car. I believe John offered to drive me up to

Boston, but I didn’t want inconvenience him any further. Because I was taking this unusual step of travelling over

1000 miles to talk to some doctors when, one would think, there must be fine

ones in Florida, this felt like something I should do myself.

Shortly after making all the appointments, my godmother, Barbara, passed away in Massachusetts. As I was never going to miss her funeral, that meant rescheduling my MRI. Luckily, they were able to give me an appointment just a week later. As it turned out, this trip would be the first of many that I would take to New England in 2024. (I’ve written about the funeral trip here).

While waiting at Logan airport for my flight back from the

funeral, I decided I needed to do more preparation before my appointments at

Dana Farber the following month. I found

another current book on Amazon, “Prostate Cancer 20/20” by Andrew Siegel, and started

reading it immediately. A lot of the

information just reaffirmed what I had already read, although there were some

new points. I was excited to see a

chapter entitled: “Should I Have Surgery or Radiation?” Unsurprisingly, the chapter does not

explicitly answer the question but gives a lot of detail about the pros and

cons of each. So I had more information

but was still undecided about what would be best for me. I looked forward to the Dana Farber

appointments to help me make that decision.

A week after getting back from the funeral, I had

my

appointment for the MRI and chest X-ray at Neuro Skeletal Imaging (or

just NSI

as they apparently prefer to be called, likely due to some corporate

rebranding

that says every company needs to go by an acronym rather than words). The scans went fine and, if I remember

correctly, as I had requested, they even played some songs by “The

Offspring”

in my headphones during the MRI.

I had requested a CD with the images so I could

take it to Dana

Farber (or wherever I wound up being treated).

I repeated the request again after my last scan and was told to

wait in

an interior waiting room. I was

apparently forgotten about as I was waiting for maybe 20 minutes or so. When someone saw me, they asked what I was

doing there. Apparently, almost everyone

had gone to lunch. When I said I was

waiting for my CD, they quickly produced it and I was on my way. Weeks later I would find the CD only

contained the chest X-ray and not the MRI.

Maybe they would have burned the MRI to CD after lunch.

When I originally scheduled my Dana Farber visits,

all three

of my appointments were supposed to be the same day, in the same

location. However, a few weeks before my

trip, they

called to say my appointment with radiation oncologist Dr. Kim needed

to be

changed. Now, I would be seeing another

radiation oncologist, Dr. Sayan, but it would be on Wednesday at the

Yawkey

Center in Brookline. I was annoyed, as

this meant having to drive into Boston twice, with the second trip

deeper into

greater Boston and in morning traffic to boot.

Also, I’d have to change my travel arrangements, but there was

really

nothing I could do and I was still looking forward to talking to Dana

Farber

doctors. As it turned out, the change of

doctors might have played a crucial role in my ultimate decision.

I started flying Southwest airlines years ago,

largely

because of their nonstop flights to secondary airports like Manchester,

NH, and

Providence, RI—my destination on this trip.

Another reason I’ve liked Southwest is because they always let

you

cancel or change flights without penalty (now, it seems they all might

do

that). So, I was able to easily change

my return flight with no cancellation fee, although the later flight

did cost

about 50 bucks more. It was easy enough

to add a day to the car rental. And, as

it turned out, I could get another day of luxury accommodations at my

brother’s

house at no additional charge.

A couple weeks after the trip changes, the day to

leave

arrived. For some reason, this particular

trip wound up being dotted with minor technical issues.

The first occurred when I was going through

security screening in Orlando. My

printed boarding pass would not scan—maybe my printer had been low on

ink.

I’m sure I got a lot of eye rolls from young folks

looking

at the old guy with a paper boarding pass.

For a second, I worried I’d have to go back and print out a new

boarding

pass at a kiosk, then get back in line.

There was a long line, so maybe I’d miss my flight, not get

another one

and miss all the appointments. Luckily,

I had the Southwest app on my phone and was able to step out of line,

fumble

through it while holding my bags, bring up my boarding pass and get

through

security. Crisis averted.

I had brought the CD which, allegedly, contained

my MRI

images and the chest X-ray that the surgeon had asked for.

However, when I actually looked at the CD after

I got to Rhode Island, I realized the label only said “chest x-ray” on

it. After borrowing a USB CD drive from my

nephew,

I was able to determine that, indeed, the imaging facility had left the

MRI off

the CD. Had I bothered to look at the CD

at any point between the day I received it and when I left on the trip,

it

likely would have been very easy to get a new, correct CD.

Now, I was over 1000 miles away and realizing

I would have no images to provide to Dana Farber before my appointments. There’s probably a lesson in there about why

I should double check stuff and not assume other people did things

correctly.

It was Sunday when I realized the problem, so I sent an email to NSI, the imaging facility, and also left them a voice mail. To their credit, NSI overnighted a corrected CD to my brother’s home and I was able to deliver it to Dana Farber before my Wednesday appointment. Ultimately, Dana Farber did their own imaging, so I’m not sure if they actually needed my CD, but at least I did get it to them.

I flew into Providence the Sunday afternoon before

my Monday

appointments. I didn’t have to be there

until the afternoon but I wanted to account for potential traffic and

my

possibly getting lost. I certainly

didn’t want to risk being late after travelling all this way. John drove me to the north side of Providence

to pick up my rental car around 10am (more about the car later).

My first two Dana Farber appointments were at the

Lifetime

Center in Chestnut Hill, where Boston College is located.

My knowledge of the west side of greater

Boston was not great, but I had been to Chestnut Hill for a Boston

College

football game with my brother John in 2008, shortly after our mother

died. His son Daniel, my nephew, was going

to school

there at the time. I remember taking the

MBTA subway in and walking to the stadium on that wet fall day. BC beat Rhode Island pretty easily.

My return trip to Chestnut Hill, 15 years after

the BC game,

was a surprisingly easy drive. After

picking up my rental car in North Providence, I got right on I-95 and

got to my

exit in less than an hour. That was even

after stopping at the first rest area to figure out how to work the

radio and attempt

to control the heater.

The facility was just a few miles off the

interstate. Too close, as it turned out,

as it came up on

me before I was looking for it and I blew right past it.

Further, the place was on Route 9, a divided

highway with no U-turns. I had to circle

back around on side streets to finally get to the facility. Turns out, leaving early for my 12:15pm

check-in time was a good idea. I was in the free parking garage in

plenty of

time.

Upon entry, everyone was required to don a mask,

as COVID

was currently in an upswing. I checked

in, got an ID sticker and received directions to where I had to go for

my

appointments. I also stopped at the

imaging department and dropped off the semi-useless CD that I brought

from

Florida that contained only a chest X-ray and not my MRI (as mentioned

in a

prior rant). I was immediately impressed

with how efficient everything was.

My first stop was to see Dr. Serzan, a medical

oncologist. From my research, I already

knew a lot of what he was saying in his introductory comments about

prostate

cancer and treatment options. He had

reviewed my biopsy results and concurred with the finding from the

initial

reading of it, so I finally got the second opinion that all the books

recommended.

He talked about the two basic options of surgery

and

radiation. With my grade of cancer, he

recommended also getting 6 months of hormone therapy if I chose the

radiation

option. This was a little disappointing

as I had hoped the cancer was small enough to not need the hormone

treatment

and the side effects it would bring. As

I already mentioned, my father had gotten hormone treatment for his

prostate

cancer since, with his advanced age, surgery or radiation were not

advisable. I believe back then—over 20

years ago—he was given estrogen. Today,

they would use Leuprolide (aka Lupron) injections and Bicalutamide (aka

Casodex)

which, incidentally, is the drug that has been used for chemical

castration of

sex offenders. The estrogen had caused

my father to have hot flashes, but also weakened his bones which led to

a chain

reaction of other problems that I discussed earlier.

Dr. Serzan told me that I would get a Lupron shot

in the

butt (not his words) prior to radiation to stop production of

testosterone. In addition, I would be

taking the Casodex pills daily to, essentially, prevent whatever

testosterone

was left from doing anything. Together

they would starve the cancer of the testosterone that “fuels” the

prostate

cancer.

The side effects—in addition to the reason they

give it to

sex offenders—could be fatigue, weight gain, mood changes and, of

course, hot

flashes, as well as more rare, more serious stuff that most medications

warn about. Since I would be only taking

the drug for 6

months, the side effects were expected to dissipate over time. Dr. Serzan would be monitoring my bloodwork

and general health during hormone treatment, if I went that route.

I still had that big document with all my notes

and

questions—in fact, it was likely bigger and had more questions than

before. Unlike my Orlando appointment,

Dr. Serzan was perfectly willing to stay as long as needed to answer

all my

questions. I think I might have been in

his office for an hour.

My next appointment, later that afternoon, was with Dr.

Wollin, a surgeon. I was already leaning

towards radiation, assuming the radiation experts told me it was feasible, but

I wanted to get as much information about all options before finalizing any

decisions.

Interestingly, Dr. Wollin said he was flattered

that I was

talking to him, since he had seen that I had met with, perhaps, the

most

world-renowned prostate surgeon in Orlando.

As with Dr. Serzan, his introductory statements about prostate

cancer

were mainly things I already knew from my research.

In response to my question about potential

side effects of surgery, he indicated that different surgeons had their

own

particular techniques, each of which might work better to prevent one

side

effect or another. This was new

information for me as I kind of assumed all surgeons did pretty much

the same

thing. Maybe if I had watched those

cringe-worthy prostate surgery videos I might have known better.

We also discussed logistics, such how long I would

need to

stay in Boston should I chose to have surgery at Dana Farber. As had been the case with Dr. Serzan, I

probably spent close to an hour with Dr. Wollin. He

answered all my questions and was willing

to spend as much time with me as I needed—unlike the world-class

surgeon in

Orlando.

After my appointments, I had planned to accompany my brother, John, to one of his presentations to promote his hiking book, Walking Rhode Island, that evening. This one would be for the Cumberland Land Trust in Cumberland, Rhode Island. Between the length of the appointments and the traffic coming out of Boston, it looked like might not make it back to Rhode Island in time to join him. I called John from traffic and gave him my Kia nav system-provided ETA and he said he would wait for me. So I made it back to his house in time to grab a snack (I hadn’t eaten since breakfast) and jump in his car to get on the road again. In addition to supporting his presentation, I was wanting to discuss what I had learned from the day’s appointments.

John’s presentation went off well, as usual, and

was

well-attended. I helped with setup and

book sales, which were quite brisk. A

big surprise was that my cousin Kim and her husband, Kevin, had driven

down

from Massachusetts for the event. It had

been I-don’t-know-how-long since I had seen them and it was great to

talk to

them. Many years ago, Kevin had gotten

radiation treatment for testicular cancer and, since I said I was

considering

that route for my prostate cancer, he offered to share his experiences

with

me. I took him up on that offer and we

had a long, very helpful phone chat a few weeks later.

|

|

My brother John's book, "Walking Rhode Island"

|

I accompanied John to a book

presentation in Cumberland, Rhode Island

|

After John’s presentation, we were able to find an

open

restaurant and I finally got to eat.

This being New England, I asked if they could put the Bruins

game on one

of the TVs. I was disappointed that they

were losing by 3 goals, but happy to talk through the day’s events with

John. As always, he was supportive of my

approach

of getting information before deciding what to do.

Because of the movement of one of my appointments

from

Monday to Wednesday, Tuesday was a “day off” for me.

I took advantage of the day by going on a

somewhat chilly morning hike with John and some of his friends to the

Barn

Island Wildlife Management Area on the Connecticut coastline. It was a really interesting 4-plus mile hike

through a

marsh and wooded areas, winding up along the coast.

You can read John’s article on the hike here.

|

|

|

Overview of Barn Island Wildlife Management Area

|

John taking notes along trail through marsh at Barn Island

|

View of ocean across the marsh at Barn Island |

|

|

Babbling brook in the woods at

Barn Island

|

View of

marshes at Barn Island

|

|

|

View across Little Narragansett

Bay at Barn Island Wildlife Management Area

|

Swans in the ocean at Barn Island

|

|

|

Me looking out over Little

Narragansett Bay at Barn Island

|

On the way home we saw this house

that looked like a castle

|

The hike was a nice start to a day which turned

frustrating

as I dealt with the third technical issue I ran into on this trip. This one involved my rental car.

To save some money, I had booked the

“Manager’s Special” at a Hertz location in North Providence. Renting a car at the airport which would have

cost over twice as much.

I figured they’d give me the cheapest, crappiest, smallest

car they had, which would be fine with me—even if it was a Yugo or a Chevette

or something. I was surprised—and a

little excited-when I arrived at the rental place to find I was actually

getting an EV, a Kia EV6. The rental

folks assured me that there were lots of places where I could get it

charged. I would need to get it charged

because it was unlikely to make it to Boston and back twice on a single charge. Plus, they would charge me $35 if I returned the

car not fully charged.

Once I figured out how to operate the car, it was actually

pretty fun to drive. I did have to stop

at the first rest area I saw to figure out how to turn the radio on and to try

to control the heat. I never actually

got the heater under control as, despite setting it to what should have been a

comfortable temperature, it was either blasting scalding hot air or leaving the

car freezing cold (this was March, so still technically winter).

The real problem came the day after my first appointments when

I tried to get it charged. At first, it looked like it would be easy as

Google showed me several charging stations that should work right in Cranston

where my brother lived. However, when I

talked to my nephew Andy, who actually has worked in the EV industry, I found

things would not be that simple.

As it turns out, the charging stations available locally

were of low kilowattage, meaning it would take at least overnight to fully

charge the car. There would be no way to

fully charge it before I would need to leave for Boston in the morning. I had thought that the worst case would be

that I would run a long extension cord from my brother’s garage or house and

get some juice into the car that way.

But that would have taken even longer and would only work if you

had a special adapter, which I, of course, did not have.

Conceding that I was going to have to pay the $35

not-fully-charged

fee no matter what, my brother, my nephew Andy and I set out to a local

charging station to at least get the car enough charge for me to return

to Boston and get back. My next surprise

was that you couldn’t just insert your credit card and start charging your

car. In fact, I thought it might just

work by plugging it in since this particular charging station was affiliated

with a local utility which advertised that the first 2 hours were free.

I couldn’t have been wronger about any of that. The only way to work the pumps was through an

app created by the company that owned the station, Chargepoint. So, while parked at the pump with my rental

EV, I downloaded the app on my clunky old phone, set up my account and entered

my credit card info. Now, I thought, I

could charge the vehicle.

I was mistaken yet again.

Shortly after all that effort I found that I needed to

enable Near Field Communications (NFC) on my phone. NFC is used to facilitate tap-to-pay

technology on a smart phone. That would

be great, except that my phone was 7 years old and did not have NFC. So Chargepoint let me download and install an

app that could never in a trillion years work on my phone. Andy was helpful, but I think he was probably

really amused or really disgusted by his uncle’s apparent technical

incompetence.

I had heard about Chargepoint from watching CNBC, the “stock

market channel.” I knew their stock had quadrupled

amid EV hysteria after the company became public but had since lost over 90% of

its value and was approaching penny stock territory. Having now had this first-hand experience

with the company, I realized why they are on the verge of bankruptcy and why

they probably deserve go out of business.

Their software might have been developed by grade school dropouts who

don’t have any idea about a basic programming concept that you should check

whether the program could even work on the device on which it is being

installed. They could have had my money (and

I wouldn’t be writing this rant) if their charging stations just took credit

cards, but they designed a system that made it absolutely impossible for me—and

likely many other potential customers—to use their product.

|

|

In order to attempt to charge my rental EV, I had to deal with Chargepoint, the company that runs the local charging stations

|

Chargepoint stock has plummeted and, from my experience, I can see why

|

But I digress.

I felt I had been defeated by “technology,” so we headed

back to my brother’s house. Andy said he

had found a faster charger at a Walmart about a half hour away. It would cost about $50. Instead of pursuing that idea, I called the

rental car place to ask if they could charge my car just a bit if I brought it to

them. They said they could not do

that. As calmly as I could, I explained

that I simply had no way to charge this car, which meant I couldn’t get to

Boston for my doctor’s appointment. I

asked if I could bring it in and swap it for a good old-fashioned gas-powered

car. I said I’d pay whatever fee and

price difference they saw fit to charge me.

They put me on hold, then came back and told me that, if I brought the

car back by 5pm (it was about 4), they’d swap it out with no additional

charges.

So I battled the traffic, got across town and brought the

car back. Waiting for me was an internal

combustion engine, several-years-old Toyota Corola that they had not had a

chance to clean yet. It was a beautiful

sight. While there, the manager showed me

how they charged their EVs. They had one

plugged into the wall with an extension cord and that special adapter. He said it took them 2 days to get the car

recharged. He also said the “Manager’s

Special” was almost always an EV. I’m

guessing that offering to rent EVs for really low prices—and not telling the

customer they’re getting an EV—is the only way they can ever actually rent one.

After I was able to swap to a car with an internal

combustion engine, the day improved. We

all had a nice dinner at Avvio Ristorante, one of Cranston’s best restaurants. A friend of Andy’s had said they had the best

scallops in town and they were probably right.

So ends my quite long digression from my initial appointments at Dana Farber.

|

|

My Wednesday appointment was at 10am, so I left Rhode Island

around 7, again fearing traffic, getting lost, etc. This time I would have to go pretty deep into

Boston. I also had to make a stop back at

the Lifetime Center, where I had been Monday, to drop off the CD that had been

overnighted to me by the imaging people in Florida. This CD actually included the MRI as it was

supposed to.

The drive up I-95 to Route 9 (again) was pretty smooth, but getting

to the actual facility was more difficult.

First, the left turn I had to take was onto Brookline Ave, a busy street

that leads to Kenmore Square and basically goes right by Fenway Park. I didn’t realize the left turn lane was

backed up a long way and found myself in the wrong lane, well past where I

should have gotten in line. Amazingly,

someone let me cut in line in front of them¸ saving me from attempting an ugly

U-turn or otherwise figuring out how to get where I needed to go. Maybe this was a sign omens were turning good:

yesterday I was able to resolve my rental car issue and today a reputedly

ruthless Boston driver took pity on a confused person with out-of-state plates.

The next obstacle was the semi-gridlocked traffic right in

front of the Yawkey Center. I eventually

worked my way into the garage and to the parking valet still with time to

spare. One of the few negative

experiences at Dana Farber was with the valet parking cashier on my way out. They were quite rude and unaccommodating of

people like me who had no idea where they were going (or what they were

doing). I self-parked the next time I drove

to this facility.

I mentioned the radiation oncologist I was originally supposed to see Dr. Kim but I wound up seeing Dr. Sayan. Dr. Kim probably would have been great also, but I took an immediate liking to Dr. Sayan. In my career I worked as a software engineer on large teams and even interviewed potential employees. I think I developed a sense for those who truly liked their work as compared to those there just there to get a paycheck. Dr. Sayan was extremely knowledgeable, as one would expect, but I could tell he also really enjoyed his work and was dedicated to it. I was quickly getting a good feeling about the route I hoped to take.

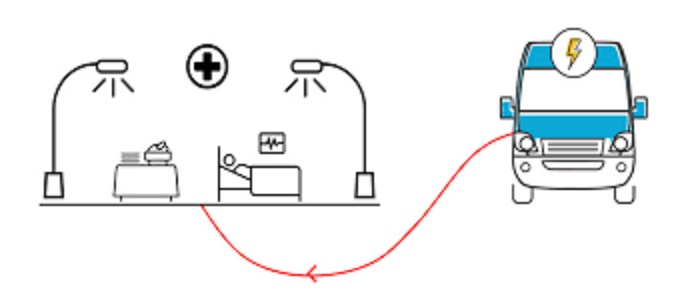

He explained that, if I chose to be treated with External

Beam Radiation Therapy (EBRT or, as I generally refer to it, “radiation”), it

would take about 5 and a half weeks.

This was a bit disappointing, as I had read of other radiation methods

that could complete treatment in much shorter timeframes. Still, this was better than the 9 weeks of radiation endured

years ago by the two people I knew who had been through it: my brother and a

former co-worker. Dr. Sayan explained

the other methods that I asked about were too new or risky for him to

employ. He also mentioned each treatment

would take only a few minutes.

Dr. Sayan also mentioned all the potential short and long

term side effects of radiation that were becoming familiar to me: things like fatigue,

urinary frequency, weak stream, having to poop more (not his words), and

impacted sexual function.

He also affirmed that radiation had been found to be just as

effective as surgery as a cure for prostate cancer. More important to my situation, Dr. Sayan

said my particular cancer could be cured with radiation. This was one of the key questions I wanted

answered.

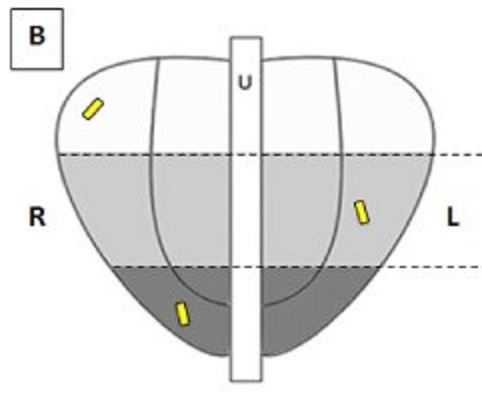

As we talked about radiation treatment, it was becoming

clear to me that Dana Farber/Mass General had all the latest technology that I

had read about. They would use

image-guided radiation, meaning, essentially, a picture would be taken before

every treatment to ensure the radiation would be directed to the correct

location. This handles situations where

the prostate might have moved between imaging and treatment. To facilitate the imaging, tiny gold markers,

or fiducials, would be placed in the prostate prior to treatment. That made me think that anyone can get

gold-plated teeth but a gold-plated prostate sounded really bad-ass.

|

|

Dana Farber also had the latest imaging technology,

including a special 3D machine that would “map” the prostate prior to

radiation. Apparently, these images

would be more detailed than the ones I had gotten in Florida. Dr. Sayan indicated this mapping would be

done about 2 weeks prior to starting radiation, meaning the images would capture

any recent changes that might have taken place in my prostate. The gold fiducial markers would be inserted

around the same time. He explained he

needed those two weeks to design a radiation plan tailored for me. That sounded impressive: my own personal

radiation plan.

Earlier I mentioned I had read about the importance of a

PSMA-PET scan, which uses a newly developed machine to find prostate cancer

anywhere in the body. The great thing

about this type of scan is that it detects whether the cancer has spread

outside the prostate. If it has,

treatment would be more difficult with more limited options and less hope for

successful cure. Having this information

up front, rather than being surprised later, seemed pretty critical to me. I wondered if such a scan, if it had existed

back then, might have benefitted someone like my brother Walt who had a

prostatectomy but still had to undergo radiation 5 years later when the cancer

showed up again.

Prior to invention of the PSMA-PET scan, a bone scan was

typically done. The problem with that is

that it doesn’t do a good job distinguishing between prostate cancer and

arthritis. When I talked to a former

co-worker who had undergone radiation treatment for prostate cancer years ago,

he mentioned that he’d gotten a scare after his bone scan “lit up” in several

areas. The initial worry was that the

cancer had spread all over but, in fact, the scan was just showing

arthritis.

I told Dr. Sayan that, when I had asked about a PSMA-PET

scan at the Orlando facility that I visited, a nurse responded that they almost

never did them and insurance would never approve one. He responded by assuring me that he could get

the scan approved. It probably helps

that, unlike other treatment facilities, Mass General actually has all this

equipment in-house and doesn’t need to send patients to an outside location.

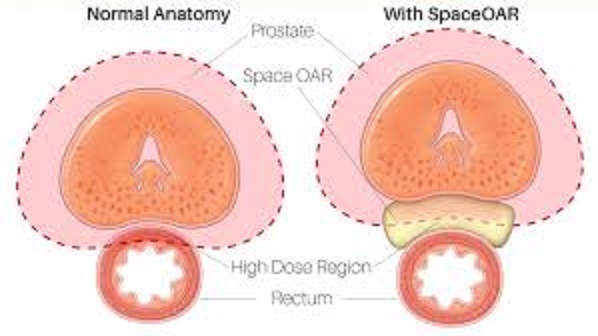

The machines actually used to deliver the radiation would also be state-of-the-art, allowing much better targeting of the cancer without unnecessarily radiating other areas. For further protection, they would use SpaceOAR, a substance that is injected to buffer the rectum from radiation. The SpaceOAR dissipates over time after it has done its job. This was another protective measure I had hoped would be used if I chose to receive radiation treatment.

In sum, everything I had read about, from the imaging to the radiation and protection from damage, could and would be used by Dana Farber to treat my cancer.

Dr. Sayan and I also talked at length about the 6-month hormone

treatment that he recommended for a Grade 3 prostate cancer like mine. I had already read about the side effects and

discussed them with Dr. Serzan, as well.

Dr. Sayan said that, if I wanted and was found to be eligible, I could

enter a clinical trial that was testing a different type of hormone treatment

drug. This other drug is typically given

to patients in more dire situations where the cancer can only be slowed and not

cured. However, it does not generally

produce the side effects that standard hormone treatment does. The trial is trying to determine whether this

other drug could be effective for radiation patients also undergoing temporary hormone

therapy. I already knew that, when

signing up for a clinical trial, they essentially flip a coin to determine if

you get in the “experiment arm” or the “control arm.” In this case, it would mean getting either

the experimental drug or the “standard of care” drugs. Of course, I’ve already discussed how unlucky I’ve been at

“coin flips” when playing Texas Hold’em, so I assumed I’d get the standard

drugs with the side effects.

Spring is the worst time of year for my allergies in Florida

and, in February and March, my eyes are often runny. I mentioned earlier that, because of COVID

concerns, everyone at Dana Farber was wearing masks. Wearing a mask, with my blocked sinuses,

generally exacerbates my allergy symptoms and, during our discussion, my eyes

were watering up. Dr. Sayan thought I

was sobbing and assured me that everything would be okay. When I told him about my allergies we had a

little laugh.

As our discussion continued, Dr. Sayan seemed to get the

sense that I was strongly leaning towards radiation and we started talking

about where I could stay in Boston for a month and a half. He mentioned there was a place, Hope Lodge,

where I could potentially stay for free, if space were available. Ultimately, Pat and I decided that, rather

than the lodge, we would stay in a hotel, but Dr. Sayan’s telling me about the

lodge further convinced me how much Dana Farber cares for their patients.

When I walked out of the meeting with Dr. Sayan I was pretty

much convinced that radiation treatment at Dana Farber/Mass General was the way

I wanted to go. However, there was still

a lot to think about, such as how to make sure Pat had everything she needed

while home alone. Also, how would lawn

mowing, pool maintenance and other chores get done? There would be a lot of logistics to figure

out such as where I would stay, how I would get around Boston and how and when I

would travel back to Florida during treatment.

It was pretty clear I’d need some help from friends and relatives with

things like rides to airports, putting out the trash and feeding the cats, to

name a few.

I thought about all this on the drive from Boston back to

Rhode Island. Because I had just the one

morning appointment, I had planned to meet John in downtown Providence for yet

another book presentation, this time at the Hamilton House, an adult learning

facility. After that, we could return my

rental car.

On the way back, I also had intended to return to the